Luxury fashion, discovering brand building principles

I invite you on a journey to discover how the two biggest companies in luxury fashion – LVMH and Kering – build their fashion brand portfolios. Over the next four months on a bi-weekly basis we will look at the principles and examples that will guide our way through their portfolios and discover what is going on.

EDIT: I have put a break on the continuous assessment as I am currently studying it within my master thesis. As soon as the thesis has been graded I will publish it fully on my blog.

Who are LVMH and Kering?

LVMH and Kering are two luxury groups that control the most relevant luxury fashion brands.

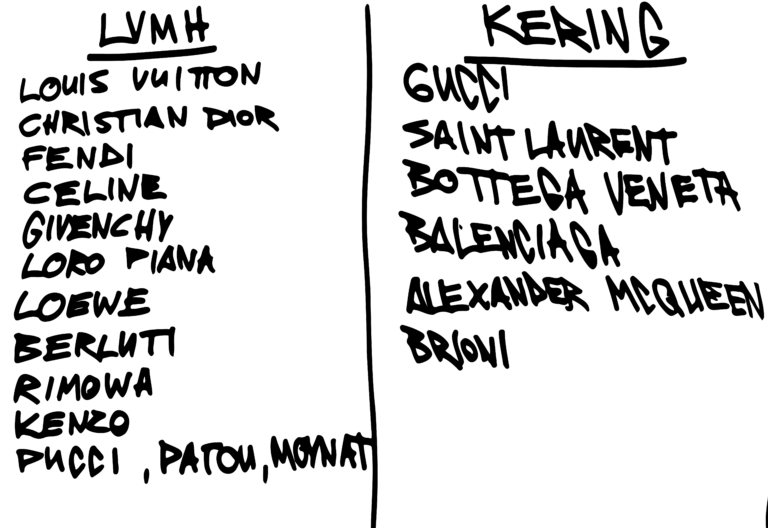

Below you find an illustration sorting the brands owned by the respective company

The wide-ranging ownership of luxury brands we see above adds up to significant revenues and profits – let’s dive into the numbers together:

In 2022 LVMH reported EUR 79bn revenues and EUR 21bn profit (27% profit margin), with +196.000 employees worldwide.

Kering reported EUR 20bn revenue and EUR 5,5bn profit (28% profit margin) in the same year with +47.000 employees worldwide1.

In terms of financial measures, they are similar, although LVMH is almost four times larger.

As we see, both achieve high profit margins and neither show any signs of stopping. Even if their businesses are built on creative and emotional brands, such margins and growth can only be achieved through rigorous rational and strategic decisions.

Developing a multitude of individual brands creates many opportunities. LVMH and Kering profit from consolidated supply chains, purchasing power with suppliers and distributors, leveraging synergies in IT and administration, and being able to distribute cash across all their brands to keep innovation high, I can ramble on and on…

However, within this series, let’s focus on brand positioning.

Searching for order – style as a common denominator

After our brief introduction to LVMH and Kering we now need to look at how we can establish a way to determine a structure across all these brands. To do so we will introduce the term target customer style, thereby applying trivial business theory to the fashion realm.

In business the “target customer” is defined as “the type of person that a company wants to sell its products or services to”.2

The companies’ activities will be aimed at selling the product to exactly that person – a target customer description should therefore be precise. Obviously consumers out of the defined range can also end up as customers, but the target customers are the ones the company or brand really caters towards.

In fashion, to define distinct target customers we can use their style. Why? Because that is a straight-forward way to make a separation – every day we see others and we either like or dislike their style. We have people we aspire to look like and others we hope to never look like, and just like that we have already made a separation. At the end of the day, we all fall into certain style groups.

How to define a style group? Take any group of people you identify with and find a shared visible symbol. Now give that group the name of the symbol and you have your style group. You identify as male, and you and your male friends wear brown belts? Well, here you go: You are the brown belt boys.

Marketers can now use that target customer style to identify the individuals they want to reach.

Of course, to be useful, the group of target customers should not be too small. Therefore, when identifying symbols to define a target customer style, it is best to look for a set of symbols and on a certain level of abstraction. Think of a group that should be able to exchange each other’s wardrobes and not just each other’s brown belts.

Finally, we can define target customer style as the abstract set of visible shared symbols that define a reasonably sized group of people. That’s the group a company wants to sell its products or services to.

How does Target Customer Style show up in LVMH and Kering’s Portfolio?

Let’s think about it like this:

What happens when I spend my money on one brand that offers the style I like (– in other words: their target customer style fits my style)? I have less money to spend on another brand that offers the same style I like.

Luckily there are more customers than just me in the market, and many also like different styles. Therefore, it makes sense for another brand to cater to another person’s style – making it the brands target customer style. This is also called differentiation.

Now you have one customer with style A spending on Brand A and another one who likes style B spending on differentiated Brand B.

To reach many customers effectively a company (like LVMH or Kering) must own many brands, each of them offering a certain style. These styles need to be different so that brands belonging to the same company do not take away each other’s revenues. Looking at the number of brands owned by LVMH and Kering, we can safely assume that they are able to reach a broad range of customers and that their brands offer different styles.

At the same time, LVMH and Kering do not want to give each other free revenue. They do not want me to spend my money on a brand not owned by them, without at least considering that there is also another brand offering it – this one owned by them of course. At this point differentiation stops and they begin competing over my budget.

What may be the principles behind LVMH’s and Kering’s portfolios?

Concluding our observations from above we can define two principles:

- Serve different target customer styles across all owned brands to be able to sell these without internally cannibalizing the performance of another brand

- Own a brand that serves a similar target customer style compared to a brand owned by the competitor

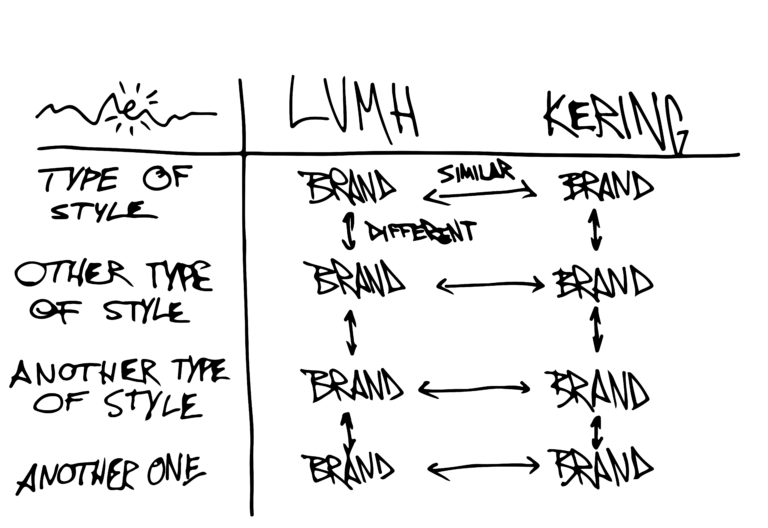

Mapping the portfolios against these principles we get the following picture

Following this theory, we should always be able to find exactly one brand within the portfolios of LVMH and Kering that fits a defined target customer style.

Does the theory truly reflect the market?

The table above illustrates the theoretical construct.

In the coming weeks, spread across multiple parts, we will look at different customer styles, matching personae, and identify the brands out of the respective portfolio that serve this style with the goal to either validate or falsify our principles for brand positioning.

Stay tuned! I am excited how it will play out and what we can discover about luxury fashion in this bi-weekly format.

For completion I want to introduce you to Richemont – another top three luxury group. Revenue: EUR 19bn, Profit EUR 3bn, Margin 17,7%, Employees +35,0001. They are not included in the assessment, as their portfolio is more focused on jewellery (Cartier, Van Cleef & Arpels, A. Lange & Söhne, etc.).

Sources:

1 Annual Reports 2021 LVMH, Kering, Richemont.

2 Cambridge Business English Dictionary (https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/target-customer).

navigate the noise with me and be first to read the latest articles